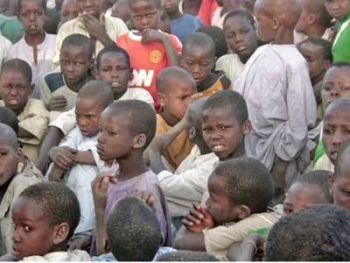

The almajinrici system which allows a person (almajiri) to leave his home in search of Islamic knowledge has unfortunately, over the years become syno

The almajinrici system which allows a person (almajiri) to leave his home in search of Islamic knowledge has unfortunately, over the years become synonymous with hunger, deprivation, insecurity, and diseases with the northern political elites allowing this aberration to fester and become a national burden.

While many almajiris are unable to break the cycle and are contented with being subjected to a life of perpetual begging, only a handful have been able to break away from the shackles of the system, and done something reasonable with their lives. Such is the story of a top custom officer (name withheld) who together with his fellow almajiri, now a law maker in the Kano State House of Assembly were able to, against all odds, break loose from a life of perpetual deprivation.

Recalling his journey from being a beggar on the streets of Kano to becoming accomplished, the custom officer didn’t mince word in capturing his ordeal in graphic details.

Life as an almajiri in Kano was very tough. I could still remember how we went about in tens begging for alms and food. It’s really not a life anyone should live. I lived it years ago and could still tell exactly how it hurts; the memory of it and the hellish experiences we had to bear. Almajiri life isn’t a life. It’s like being dead-alive. I lived that life.

I was ten when I decided to remove the cloak of destitution and face life squarely. It still remains the turning point in my life and the wisest decision I’d ever taken. I could still remember vividly what led me to take such a decision one afternoon. It was at Sabon Titi Kano. We were nine in number. We had trekked all the way from Bida Road. Ali, my best friend was saying something about how very unfair it was that girls were not allowed to wander about begging as boys did. He said something about girls being lucky and fortunate because they were not subjected to the demeaning life that we lived.

“But you don’t have to think that way,” I said. “You know that if you lived a good life here on earth, you surely would enjoy in heaven when you die.”

Ali had always thought differently. He was thirteen years old. Several times he would tell me that we should elope. He said he didn’t like the way the Mallami treated us. According to him, we were treated as slaves and it was very unfair. Ali was the first ever almajiri I had seen who did not like his being a poor beggar. He always compared himself with the children of the rich.

“Do you think Mallam Ladan will ever allow his own children to move about aimlessly in the streets begging as we do?” he often asked me. “He will never do a thing like that. His children eat good food and go to the white man’s school but we don’t. And every day, we take money that we make from begging to him. That is not fair.”

No one hated Mallam Ladan as much as Ali did at that time. Mallam Ladan had always said that Ali was rebellious and that he behaved like an infidel. One day, and according to him, all infidels would never gain paradise where there were lots of merriments. I remembered one day Ali had asked a question during our usual group recitation of the holy book and Mallam Ladan, red with indignation ordered that Ali should be whipped. According to him, Ali had asked a blasphemous question. Since then, Ali expressed his displeasure and irritation about the Mallam secretly to me.

So, the day I finally made up my mind to quit almajarinci was at Sabon Titi. We gathered around a very busy canteen owned by a woman from Lafia whom everybody referred to as Mama Nassarawa. She had a very large open space with huge patronage. Most often when any of her many customers ate to their fill and there was leftover, we would swing into action. It was usually like warfare. Our survival-of-the-fittest lives were hugely dependent on the miserable remnant from the food Mama Nassarawa’s customers left in their plates.

Keenly, we watched from a close distance as the customers ate. Our eagle eyes moved from customer to customer and hand to hand. Contrary to what people think, the almajiri usually had more than enough to eat but we ate like swine; unhealthy and without control. There was a very beefy fellow eating a fat meal. He had so many pieces of meat in his soup which attracted some of us; I especially had had the rare opportunity of eating meat and fish many a time. This would happen when some people barely touched their food before passing it to us. I had often wondered then why some people would eat only little food and be satisfied. Ali had also wondered too. He had told me once that he had never had a full stomach. He would emphasize further that until his hand got tired of conveying the food from the plate to his mouth, he would always continue to eat.

The beefy fellow at Mama Nassarawa made me have a rethink that day. He was eating pounded yam. Ali and I fixed our eyes on him. Suddenly, I noticed something rather strange. This fat customer was drooling like a toddler. Saliva dropped from his mouth into his soup as if there was a burst tap in his throat. We were supposed to take a dive for the leftover of that food! Mere looking at him made me sick.

“Ali, can you see what is happening?” I muffled. “Can you see the way that man’s saliva fall freely into his soup?” Ali smiled. “Abubakar, I am really shocked at what you are saying.” Do you mean to tell me that you haven’t seen something like this before? I can swear by my life that most of these people there are sick. And because we eat what they leave behind, we are very likely to share in their misfortune since most illnesses are contagious. Abu, we are walking corpses.”

His response gave me goose pimples. That was the day Ali and I made up our minds to go out there and change our stories and destinies. In life, Allah gives us all equal opportunities. He gives us same air to breath and same time; twenty four hours daily to live in. No one has more time than others. What we do with the time and how we choose to breath is dependent on the choices we make. Some make good choices and others don’t.

“Ali,” I muttered coldly, “may Allay forbid that I eat the leftover food from that man.”

For the first time since we became friends, Ali hugged me. “Abu, you have said a noble thing. If you mean what you have said then we must elope. We must leave now. There’s nothing as sweet as freedom.”

We both separated from the other boys that day and threw our beggarly bowls away.

That night, we found a Dangote trailer which was about leaving for Lagos. It had just the driver and his conductors. Ali and I sneaked into it when no one was watching and in no time, our journey out of Kano began. It was not until we got to Suleja that the driver and his conductor found us in their vehicle. They had stopped along the Abuja-Kaduna Road to refuel and eat. It was past ten. The conductor pointed his torch and saw us sleeping in a corner.

“Subanalahi!” he exclaimed rather surprisingly. “Ahmadu come and see these miserable elements sleeping in our vehicle.”

The driver climbed up and found Ali and me in the truck. I was shocked when he asked if we had eaten. Ali and I replied in unison that we had not eaten. He ordered us to climb down the truck. We followed them to a food vendor’s place where he bought us good food. It was the very first time that we would be having such good meals without begging for it. After we had told him our story, he advised that we find a mosque in Suleja to spend the night.

“If you go to Lagos, you will suffer. The people there will not help you. They will tell you to go to your parents. You are still in the north. People here will understand why you are out of school at this age. This is why you should be here and not in Lagos. I will advise that you get shoe shining kits and begin to render services to people. Whatever you make could feed you and you will have a little to save for school.”

He gave us two hundred naira each and reiterated that we must use it wisely. The money at that time was big. How Ahmadu understood us and promptly decided to come to our aid still baffles me to this day. When their vehicle left, we spent the night at Kaduna Road on a plank beside a parked lorry. At dawn, we went to a nearby stream and bathed. It really felt so good that day because it seemed we were no longer under anyone who would dictate for us. That day, we found some cobblers and they told us how to go about getting all the kits and how to do the job. In three days, we were already dexterous shoe shiners. Days later, we were brilliant cobblers.

On our twelfth day on the job, an Igbo trader whom we went to his house to polish his shoes – nineteen pieces in all – took pity on Ali and me and ask a few questions.

“You people are too young to do this job you are doing,” he said. “Don’t you have plans to go to school?”

Ali and I told him that we had already bought all our note books.

“It’s our uniforms that are left for us to buy,” I told him.

He was leaning on his car and from the way he kept nodding; it was obvious that he was impressed with what we’d told him. He insisted we show him the books we had bought. Ali quickly ran to the shop where we had already paid for the books but were yet to be supplied to fetch them. In no time, he was back with them. That day after we had finished polishing his shoes, Mr. Okafor gave us money to buy our uniforms. He said he would have taken us and given us a place to stay but that we were too young and he could be accused of abduction.

“Come here when your uniforms are ready,” he told us.

That was how Allah used Mr. Okafor to change our story in 1992. He took us to a public primary school and registered us. Some people are angels and when you are lucky to meet them, they don’t care what your tribe or religion is before they choose to help you. Mr. Okafor was such a person. Ali and I began to sleep in one of his warehouses at night with some of his workers – mostly Hausas who help to offload his goods. His wife treated us like her own children. She would give us food and some of her children’s old clothes.

Tragedy struck in the year2004 when Ali and I were at ABU Zaria. Mr. Okafor had an accident on his way to his village and died. I thought this would affect us but Obinna, his eldest son took over his fabric business and still carried on as if nothing had happened. The relationship we had with the family blossomed. When we returned from school, we would work in one of their warehouses until the holiday was over. There was never a time we called Obinna and told him we needed money and he didn’t respond.

After my service in 2010, I joined the custom service while Ali through one of his friends whom he met in school became a politician. He is a lawmaker in his state house of assembly. He is doing great. We are both doing great and still good friends. And we are still very close to the Okafors. Ours is a relationship that would last until the day Allah calls us.

Our story has taught me that the saying ‘man is the architect of his own fortune,’ is very true. And also, when there’s a will, there surely will be a way. Don’t let anyone deceive you, there is light of every dark tunnel for everyone. We only remain in the darkness of the tunnel because we are just too scared to approach the light. if we make a move, we surely would be out of the tunnel.

I got married in 2015 and Obinna and his mother attended the wedding. They were also in Ali’s wedding too a year before. When we fight over tribe or religion, we do so because we are largely ignorant of our existence and how Allah can use us as angels to help one another. Humanity should always count because we are all one and the same. It is needless for us to keep pointing guns and raising daggers at one another.

Japheth Prosper is an accomplished writer